Aristotle’s Four Causes is an important fourfold that seems to be the basis for many of the fourfolds, both original and not, presented in this blog. Two of the causes, efficient and material, are acceptable to modern scientific inquiry because they can be thought of as motion and matter, respectively, but the other two causes, formal and final, are not. Why is that?

Aristotle’s Four Causes is an important fourfold that seems to be the basis for many of the fourfolds, both original and not, presented in this blog. Two of the causes, efficient and material, are acceptable to modern scientific inquiry because they can be thought of as motion and matter, respectively, but the other two causes, formal and final, are not. Why is that?

The formal cause is problematic because the formal is usually considered to be an abstract concept, a construction of universals that may only exist in the human mind. The final cause is also problematic because it is associated with the concept of telos or purpose. There, too, only human or cognitive agents are allowed to have goals or ends. So for two causes, efficient and material, all things may participate in them, but for the two remaining, formal and final, only agents with minds may.

These problems may be due to the pervasive influence of what the recent philosophical movement of Object Oriented Philosophy calls correlationism: ontology or the existence of things is limited to human knowledge of them, or epistemology. The Four Causes as usually described becomes restricted to the human creation and purpose of things. Heidegger’s Tool Analysis or Fourfold, which also appears to have been derived from the Four Causes, is usually explained in terms of the human use of human made things: bridges, hammers, pitchers. Even scientific knowledge is claimed to be just human knowledge, because only humans participate in the making of this knowledge as well as its usage.

Graham Harman, one of the founders of Speculative Realism of which his Object Oriented Ontology is a result, has transformed Heidegger’s Fourfold so that it operates for all things, and so the correlationism that restricts ontology to human knowledge becomes a relationism that informs the ontology for all things. Instead of this limiting our knowledge even more, it is surprising what can be said about the relations between all things when every thing’s access is as limited as human access. However, this transformation is into the realm of the phenomenological, which is not easily accessible to rational inquiry.

I wish to update the Four Causes, and claim that they can be recast into a completely naturalistic fourfold operating for all things. This new version was inspired by the Four Operators of Linear Logic. Structure and function are commonplace terms in scientific discourse, and I wish to replace formal and final causes with them. It may be argued that what is obtained can no longer be properly called the Four Causes, and that may indeed be correct.

First, let us rename the efficient cause to be action, but not simply a motion that something can perform. I’m not concerned at the moment with whether the action is intentional or random, but it must not be wholly deterministic. Thus there are at least two alternatives to an action. I’m also not determining whether one alternative is better than the other, so there is no normative judgement. An action is such that something could have done something differently in the same situation. This is usually called external choice in Linear Logic (although it makes more sense to me to call it internal choice: please see silly link below).

Second, let us call the material cause part, but not simply a piece of something. Instead of the material or substance that something is composed of, let us first consider the parts that constitute it. However, a part is not merely a piece that can be removed. A part is such that something different could be substituted for it in the same structure, but not by one’s choice. Like an action, I am not concerned whether one of the alternatives is better than the other, but only that the thing is still the thing regardless of the alternative. This is usually called internal choice.

Next, we will relabel the formal cause to be structure, but not simply the structure of the thing under consideration. Ordinarily structure is not a mere list of parts, or a set of parts, or even a sum or integral of parts, but an ordered assembly of parts that shapes a form. Ideally structure is an arrangement of parts in space. However, in this conceptualization, structure will be only an unordered list of parts with duplications allowed.

Last, instead of final cause we will say function, but not simply the function of the thing as determined by humans. Ordinarily function is not a mere list of actions, or a set of actions, or a sum or integral of actions, but an ordered aggregate of actions that enables a functionality. Ideally function is an arrangement of actions in time. However, like structure, function will be only an unordered list of actions with duplications allowed.

As we transform the Four Causes from made things to all things, both natural and human-made, we will later examine how that changes them.

References:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speculative_realism

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Object-oriented_ontology

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graham_Harman

http://wiki.cmukgb.org/index.php/Internal_and_External_Choice

[*6.144, *7.32, *7.97]

<>

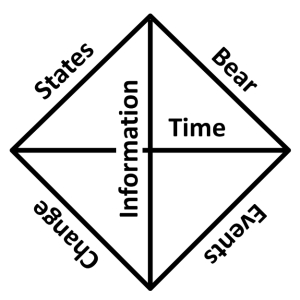

Schopenhauer’s Four Classes that comprise his Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason are diagrammed above. Becoming, Knowing, Being, and Willing are these classes.

Schopenhauer’s Four Classes that comprise his Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason are diagrammed above. Becoming, Knowing, Being, and Willing are these classes.