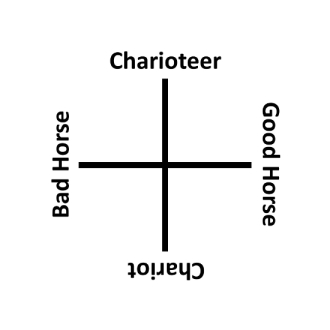

At the risk of being labeled a neo-platonist, another triad of Plato’s that is often discussed is that of the Allegory of the Chariot. This analogy is supposed to bring insight into the workings of the human soul and consists of two horses, one good and one bad, and the charioteer whose duty is to control them. You never hear about the chariot itself (but it is always pictured), but it is required to have a chariot, after all. The charioteer isn’t just standing on the backs of the horses, like Jean-Claude Van Damme doing his epic split, although that would be cool. (They do this at the circus, and I know I’ve seen it in old gladiator movies when the chariot loses a wheel and the charioteer has to cut away the chariot.)

At the risk of being labeled a neo-platonist, another triad of Plato’s that is often discussed is that of the Allegory of the Chariot. This analogy is supposed to bring insight into the workings of the human soul and consists of two horses, one good and one bad, and the charioteer whose duty is to control them. You never hear about the chariot itself (but it is always pictured), but it is required to have a chariot, after all. The charioteer isn’t just standing on the backs of the horses, like Jean-Claude Van Damme doing his epic split, although that would be cool. (They do this at the circus, and I know I’ve seen it in old gladiator movies when the chariot loses a wheel and the charioteer has to cut away the chariot.)

Thus, unless you want to change the nature of the analogy, the chariot is required for everything to be connected together. This fourth material component completes the triad into a fourfold, and I place it at the lowest, fundamental position where I added The Real to The Beautiful, The True and The Good.

And of course everyone knows that Bad Horse is the Thoroughbred of Sin!

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chariot_Allegory

[*8.86]

<>