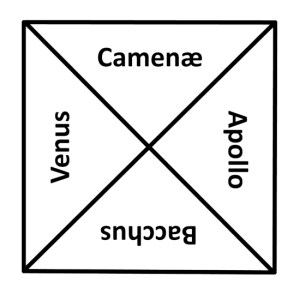

In Plato’s Phaedrus, this “fourfold vision” refers to four distinct types of divine madness or inspiration; and being of divine origination are associated with various Greek gods. These are: prophecy from Apollon (later, Roman Apollo), mystic rites (telestic madness) from Dionysus (Bacchus), poetry and arts from the Muses (Camenæ), and love from Aphrodite and Eros (Venus and Cupid). These different forms of divine madness are seen as beneficial blessings and essential for a fulfilling life, crucial for living well and having a deeper connection to truth and beauty.

Also in the Phaedrus is Plato’s theory of the soul, most famously utilizing the metaphor of a chariot driven by two horses. The four types of divine madness represent different ways the soul can be uplifted. They are powers that can help guide the charioteer, steering the soul towards its higher purpose. If the soul follows the divine, the charioteer can ascend to the “plain of truth” (i.e. the realm of Plato’s Forms.) If not, the soul falls to earth in human form. The better the soul has seen truth, the higher will be its place in its “next” life.

It’s kind of odd that the charioteer is supposed to embody Reason, in order to steer the chariot’s horses properly, and yet there is no divine madness specifically associated with reason. Where is Athena (Roman Minerva), to aid the soul in its journey, as a guide for Reason? Perhaps Plato thought that Apollon could serve double duty, as he was thought to also symbolize reason as well as prophecy. Or perhaps the very notion of “divine madness” should not be associated with reasoning and logic. I disagree.

The writings of Benjamin Labatut come to mind as showcases of the “divine madness” of reason and logic. Various persons of science and mathematics are written about in a pseudo-bibliographical way: the mathematician Alexander Grothendieck, the computer scientist John von Neumann, and others. Other writers have also written about those that live in the highest realms of logic and mathematics: Kurt Godel, Grigory Perelman, etc. Their intellect may put them close to a form of madness.

Note:

I’ve chosen the Roman names for these Greek gods for the sole reason that they fit better in my diagram. I hope it’s not too confusing.

Further Reading:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phaedrus_(dialogue)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muses

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjam%C3%ADn_Labatut

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Grothendieck

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_von_Neumann

Matthew Shelton / Divine Madness in Plato’s Phaedrus

https://www.academia.edu/118753337/Divine_Madness_in_Plato_s_Phaedrus

Katja Maria Vogt / Plato on Madness and the Good Life

Click to access paper-vogt-plato-on-madness-and-the-good-life.pdf

<>