Speaking of paradoxes, the Banach-Tarski Paradox is an interesting theorem in mathematics that claims that a solid 3-dimensional ball can be decomposed into a finite number of parts, which can then be reassembled in a different way (by using translation and rotation of the parts but no scaling is needed) to create two identical copies of the original structure. The theorem works by allowing the parts of the decomposition to be rather strange.

Speaking of paradoxes, the Banach-Tarski Paradox is an interesting theorem in mathematics that claims that a solid 3-dimensional ball can be decomposed into a finite number of parts, which can then be reassembled in a different way (by using translation and rotation of the parts but no scaling is needed) to create two identical copies of the original structure. The theorem works by allowing the parts of the decomposition to be rather strange.

One of the important ingredients of the theorem’s proof is finding a “paradoxical decomposition” of the free group on two generators. If F is such a free group with generators a and b, and S(a) is the infinite set of all finite strings that start with a but without any adjacency of a and its inverse (a^-1) or similarly b and b^-1, and 1 is the empty (identity) string, then

F = 1 + S(a) + S(b) + S(a^-1) + S(b^-1)

But also note that

F = aS(a^-1) + S(a)

F = bS(b^-1) + S(b)

So F can be paradoxically decomposed into two copies of itself by using just two of the four S()’s for each copy. Both aS(a^-1) and bS(b^-1) contain the empty string, so I’m not sure what happens to the original one. One might think that aS(a^-1) is “bigger” than S(a) but they are actually both countably infinite and so are the same “size”.

The generators a and b are then set to be certain 3-dimensional isometries (distance preserving transformations which include translation and rotation). The rest of the theorem requires further constructions that may be of interest, as well as needing the Axiom of Choice or something like it. It is also curious that the paradox fails to work in dimensions of 1 or 2.

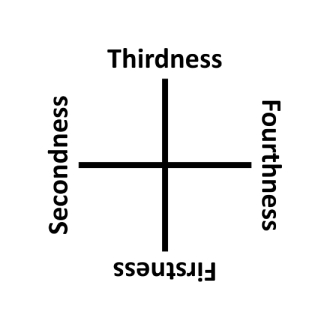

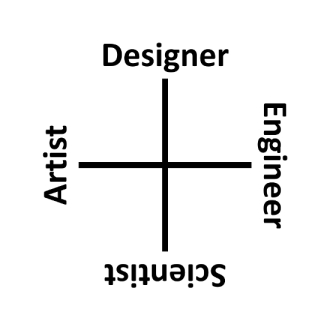

The diagram above tries to list the beginning of each of the sets S(a), S(b), S(a^-1), and S(b^-1). The empty string can be thought to occupy the center of the diagram but it is either not shown because it is empty, or it is shown as being empty. Alternatively one could create a more general fourfold with the aspects of structure, (paradoxical) decomposition, parts, and reassembly.

References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banach%E2%80%93Tarski_paradox

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paradoxical_set

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Axiom_of_choice

Click to access thesisonline.pdf

[*9.124, *9.125]

<>