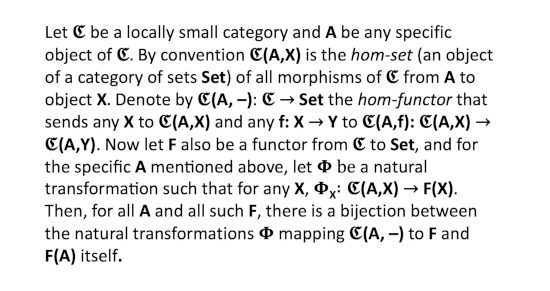

The alethiometer, an important fictional artifact in Philip Pullman’s two fantasy trilogies His Dark Materials and The Book of Dust, is a “truth-telling” device that might well have been inspired by the combinatorial art of Ramon Llull. While most users need years of study and reference books to read the alethiometer, the young heroine Lyra can understand it intuitively because of her innocence and her seeming ability to communicate with the mysterious “Dust”.

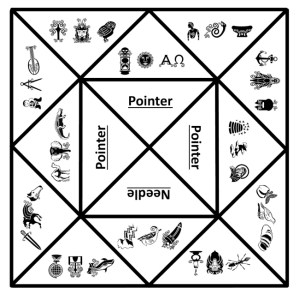

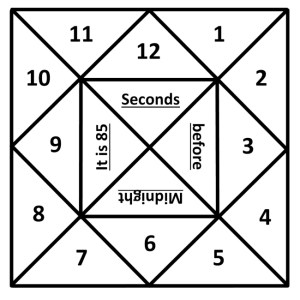

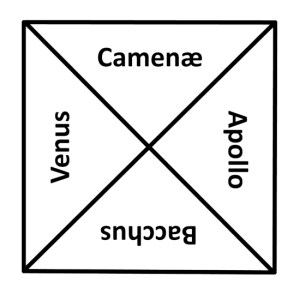

Each alethiometer (of the six made) has 36 symbols on its face, and three pointers that can be set to one symbol each. The three symbols pointed to are intended to frame a question or problem that the user has in mind. A fourth pointer is a needle that freely moves, pointing to one symbol or a sequence of them, and those should represent the answer to the query. The 36 symbols are familiar entities, but their meanings are not straightforward.

In the first trilogy, Lyra could operate an alethiometer readily, and use its power to help her navigate her way through a multi-verse of dangers, enemies, and goals. The first trilogy was more like excellent juvenile literature, in that the heroine was able to overcome hardships and achieve the outcome that she thought was best under the circumstances, even though it wasn’t what she wanted to happen. Nevertheless, it ended in a heartbreaking yet satisfying way.

In contrast, the second trilogy was closer to an adult story, not as tidy in its themes or plot lines, and with the lack of a neat resolution. As she grew out of childhood in the second trilogy, she struggled with reading the alethiometer. This was either because her lost innocence, or because adults don’t usually have as much connection to “Dust” (being enclouded by the Dust that surrounds them), or because of her estrangement to her personal daemon or soul-spirit.

In this age of blatant lies and misinformation, would that we all could have the power to discern truth from falsehoods, to consult our very own Oracle of Truth. Some think that AI driven by Large Language Models can give us access to veridic and factual knowledge, and perhaps it can. But it seems that AI can be manipulated to bias its “thinking” any which way you like. Easy access to the truth and easy determination of lies may just be a pipe dream of childhood.

Further Reading:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/His_Dark_Materials

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Book_of_Dust

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dust_(His_Dark_Materials)

https://academic.oup.com/book/59756

Click to access alethiometerchart-form-glossaryofmeanings.pdf

[*14.136, *14.142-143]

<>